Ally Selby (How the #1 picks went from hero to zero in just 6 months, 12 July) reckoned that the January-March quarter was “tough, tiresome and damn it, sometimes terrifying.” April-June, she added, was even worse: “Only three out of Australia’s (18) finest stockpickers’ highest conviction calls are in the black, while the rest have slid (some more violently than others) into the red … The total return of our fundie favourites now stands at -30.99% (inclusive of dividends, capital gains and currency movements), far worse than the -3.15% total return that I hesitantly revealed in the first quarter” (see also Ye-Qun Feng, How Livewire readers’ most-tipped ASX shares are tracking in 2022, 15 July).

In sharp contrast, for Leithner & Company (hereafter, “LCO”) the January-June half-year wasn’t particularly demanding – or even eventful. It certainly wasn’t terrifying; if anything, it was rather satisfying!

During the half-year we generated a modest but nonetheless positive total return for our shareholders. Unlike many others, we didn’t merely avoid a significant short-term loss: our very high levels of cash and equivalents, plus today’s lower prices (and the possibility of even more attractive ones in the current half-year and beyond), bode well for our investors’ long-term results.

Short and long term: three implications

Our results differ diametrically from most others’ because our mentality, philosophy, objectives, and operations bear little resemblance to – and are sometimes the diametric opposites of – the mainstream’s.

At the beginning of this year, the herd was overconfident (see Why you’re probably overconfident – and what you can do about it). By the end of June, its emotions had lurched towards anxiety (and apparently even terror); in contrast, throughout the half-year, our emotions remained unruffled (see Successful investors are stoics). And our brains remained sceptical: we focused upon risks that others slighted or ignored (see Australia’s bogus boom and Three risks you can discount – and one you can’t), and ignored distractions that obsessed the crowd (see Decarbonisation: A doubter’s guide for conservative investors).

Three implications ensue from LCO’s operations:

- We’re investors, not stock-pickers – there’s a big difference, which I explain below – and you should therefore shun stock-picking and ignore stock-pickers;

- When it takes the form of implausible gains, short-term outperformance doesn’t promote long-term outperformance; if anything, it hinders it. For the sake of your long-term results, you should avoid short-term “top performers.”

- What’s most important isn’t how much investors gain during the artificial boom; it’s how much they avoid losing during the genuine – and inevitable – bust. Mind your “downside” and the “upside” will tend to mind itself.

Why We Welcome Corrections, Bear Markets, and Financial Crises

Most people intensely dislike even modest downdraughts such as the ones that occurred in January-June. More generally, the mainstream regards financial markets’ fluctuations as bad, corrections as undesirable, panics as intolerable and bear markets as unendurable. In sharp contrast, LCO enjoys them. That’s because they greatly boost its long-term outperformance.

What’s most important isn’t how much investors gain during the artificial boom; it’s how much they avoid losing during the genuine – and inevitable – bust. If they mind the “downside” then the “upside” tends to mind itself.

That’s why we’d welcome a bear market: it’ll enable us to deploy more of our considerable liquidity to purchase quality equities at sensible or even bargain prices.

Asset Allocation: Graham’s “75-25 Rule”

Most investors know that Warren Buffett is arguably the world’s greatest investor, and that Benjamin Graham (1894-1976) was his teacher, employer and mentor. Some also know that Graham was the co-author (with his academic colleague, David Dodd) of the seminal textbook Security Analysis (1934) and the sole author of The Intelligent Investor (1949). A few have even read the latter book (virtually nobody, it seems, has read the former). And only a handful practice Graham’s approach to asset allocation:

“We have suggested as a fundamental guiding rule that the investor should never have less than 25% or more than 75% of his funds in common stocks, with a consequent inverse range of between 75% and 25% in bonds. There is an implication here that the standard division should be an equal one, or 50-50, between the two major investment mediums.”

Graham was equivocal about varying a portfolio’s percentages of bonds, stocks, etc., in response to market conditions (“tactical asset allocation”). Consequently, he was able to “give the investor no reliable rules by which to reduce his common-stock holdings toward the 25% minimum and rebuild them later to the 75% maximum.” Our application of Graham’s approach to asset allocation draws from another of his insights. He contrasted the “enterprising” investor (who is willing “to devote time and attention to securities that are sounder and more attractive than the average”) from the “defensive” investor (who “will place his chief emphasis on the avoidance of serious mistakes or losses”).

Importantly, these categories aren’t mutually exclusive. Hence LCO is a “defensive-enterprising” investor.

LCO is highly defensive in the sense that we devote more effort to avoiding loss than to achieving gain. In other words, in order to minimise our “sins of commission” we willingly accept “sins of omission.” We’re also very aggressive in the sense that we devote considerable time and effort to the search for and research of attractive companies and their securities (particularly stocks).

The problem is that we seldom find them at prices which meet our stringent criteria. When we do, we buy – regardless of others’ views, and without regard to the “consensus” (of which more below). Most of the time, when the prices of these companies’ securities aren’t attractive, we plough incoming cash (whether from new investors, income from investment operations, etc.) into short-term bonds, deposits, etc.

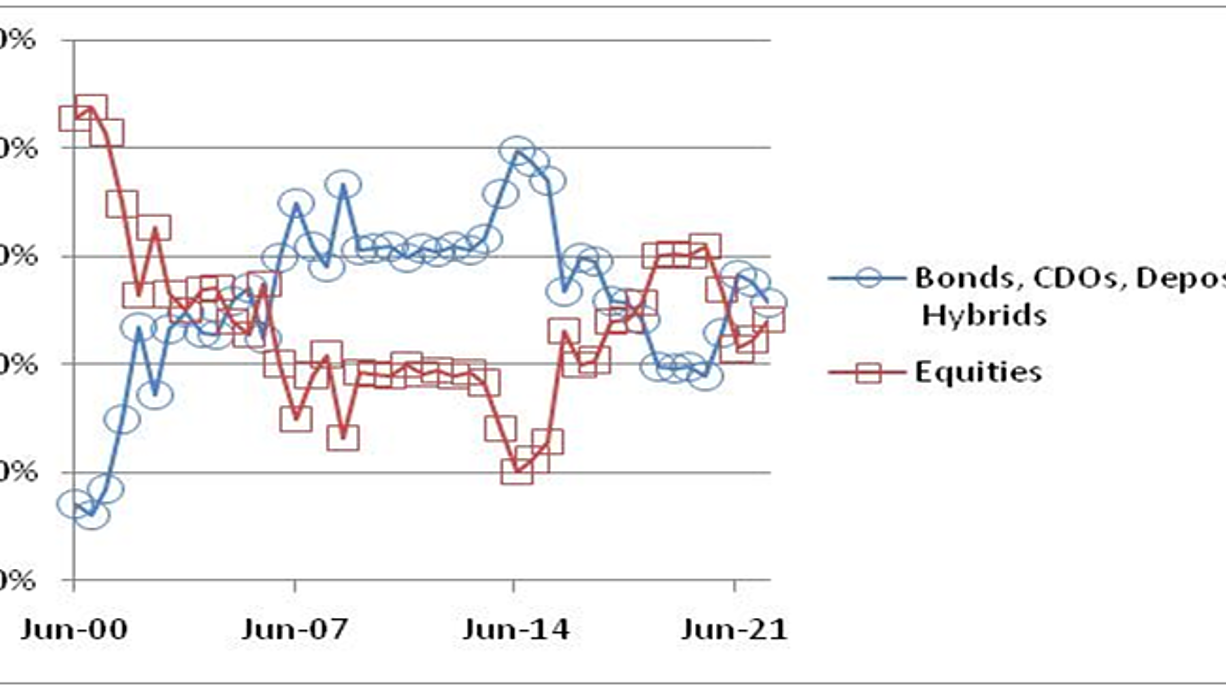

Figure 1 plots LCO’s asset allocation at each half-year since our formation in 1999. Its definition of “bonds” is liberal: it includes Collateralised Debt Obligations (CDOs) whose prices collapsed (prompting us to buy) during the GFC, cash at-call and on deposit, and hybrid securities.

Figure 1: LCO’s Asset Allocation, Half-Yearly, June 1999-June 2022

We’ve generally adhered very closely to Graham’s “standard division.” On average, since 1999 LCO’s portfolio has comprised 52.6% bonds and related securities and 47.4% stocks. We’ve also followed his “fundamental guiding rule” – not counting our first year of operation, only in CY14 did our allocation to non-equities exceed 80% (and equities’ allocation fall below 20%).

From 1999 to 2014, the allocation to equities fell. During the next six years it rose, and since 2019-2020 has fallen. On 30 June 2022, it approximated its long-term average.

Varied Sources of Income

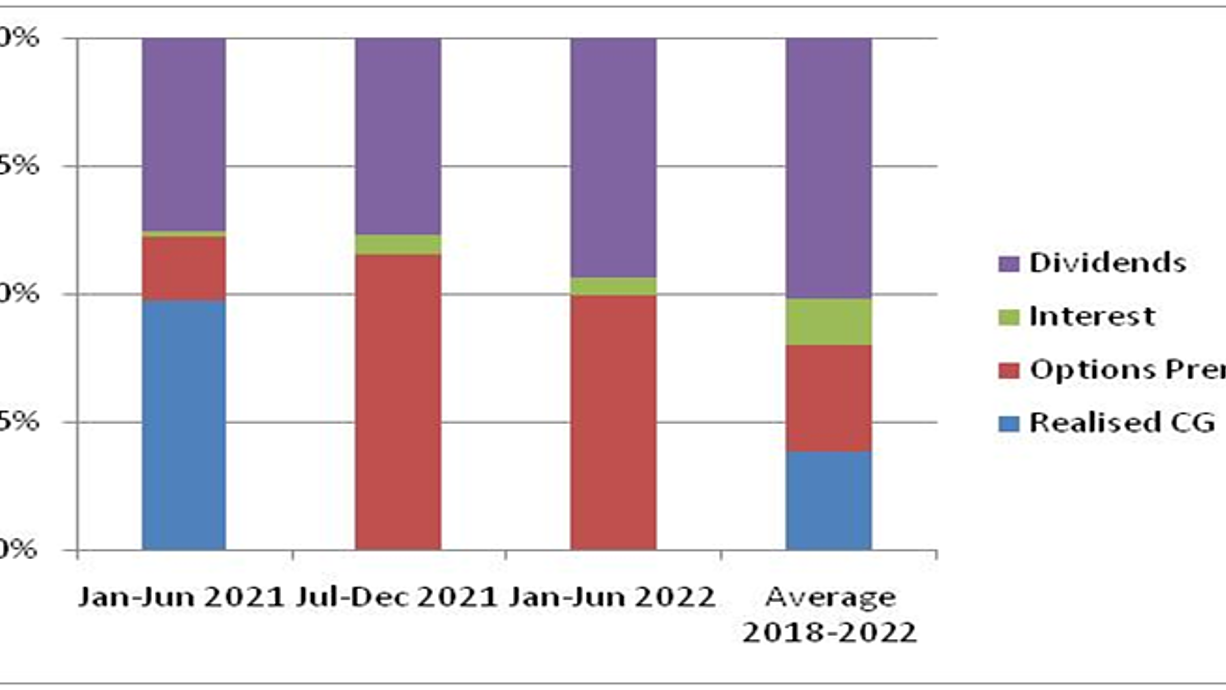

LCO’s portfolio generates income from four sources (Figure 2). Dividends have provided the major (and a continuously-significant) percentage: they comprised 47% of total income in January-June 2022, and have averaged 51% during the half-years since 2018. Dwindling rates of interest have sharply decreased the share of income derived from payments of interest: although it’s averaged 9% over the past five years, interest comprised just 4% of income in the most recent half-year.

Figure 2: LCO’s Four Sources of Income, Recent Half-Years and Five-Year Average

LCO receives premiums from options contracts (see below) and realised capital gains intermittently, that is, as opportunities arise. Falling markets tend to boost premiums from options (50% of income in the most recent half-year, and an average of 21% over the past five years), and rising prices of the stocks LCO owns eventually generate realised capital gains (0% in the most recent half-year, 48% in the half-year to 30 June 2021 and an average of 19% since 2018).

LCO’s Very Conservative Use of Derivatives

A “derivative” is a contract that can under certain conditions require one of its parties to outlay money to the other. The amount derives (hence the name) from a predetermined criterion such as the price of a bond, commodity, currency or stock, the level of a market index, etc.

Warren Buffett has stated repeatedly that derivatives can be very dangerous. Most famously, in 2002 he declared: “In our view, … derivatives are financial weapons of mass destruction, carrying dangers that, while now latent, are potentially lethal.” The GFC vindicated his concerns. Nonetheless, for decades Berkshire Hathaway has used derivatives extensively (so did Graham-Newman Corp. in the 1930s-1950s).

In 2008, Buffett told his shareholders: “Considering the ruin (I feared in 2002), you may wonder why Berkshire is a party to 251 derivatives contracts (whose face value exceeds $37 billion) … The answer is simple: I believe each contract we own was mispriced at inception, sometimes dramatically so … Our derivatives dealings require our counterparties to make payments to us when contracts are initiated … As of yearend, the payments made to us less losses we have paid – our derivatives ‘float,’ so to speak – totaled $8.1 billion. This float is similar to insurance float: If we break even on an underlying transaction, we will have enjoyed the use of free money for a long time.” In an interview later in 2008, Buffett added:

“We’ve used derivatives for many, many years. I don’t think derivatives are evil, per se, I think they are dangerous. I’ve always said they’re dangerous … But uranium is dangerous, and I (walked) through a nuclear electric plant about two weeks ago. Cars are dangerous …”

By that sage conception, equities, too, are dangerous. LCO practices Buffett’s view: if used recklessly, financial instruments including derivatives can cause colossal losses; but if used conservatively, they can be powerful generators of income.

Like Berkshire’s, LCO’s derivatives require that our counterparties pay premiums to us when these contracts commence. We usually enter into them when counterparties are nervous (or panicking); hence their payments to us can be considerable. These counterparties are jumpiest when markets are plunging; hence our derivatives operations generate the highest income in falling markets.

Unlike Berkshire, LCO enters exclusively into arrangements which reference stocks or bonds that it already owns (or seeks to own and is prepared to hold indefinitely). It only writes “covered” call options, that is, agrees (if predetermined conditions occur) to sell securities it already owns. And it only writes “put” options over companies whose shares it seeks to own at “strike” prices it regards as bargains. These obligations are always fully “cash collateralised:” if counterparties simultaneously exercise all of their options, LCO’s “at-call” cash is more than sufficient to meet these obligations. In these and other respects, our derivatives operations have always been extremely conservative.

Implications

Shun Stock-pickers, Their Tips and “Keynesian Beauty Contests”

I’ve deliberately said nothing about particular securities that LCO presently owns, once held or in the future will seek to acquire (see, however, What ASX stocks would Warren Buffett buy in 2022?). That’s because such details are relatively unimportant: asset allocation (the decision that a portfolio will comprise x% bonds, y% stocks, etc.) is generally a much more significant determinant of long-term returns than security selection (the decision to buy security A or sell security B, etc.).

Yet one general and crucial point about the selection of securities follows from what I have said: LCO buys and sells on the basis of its own comprehensive analyses – and NOT our or others’ superficial guesses about these securities’ present or future popularity. This might sound blandly conventional; in truth, it’s not just highly unusual: it’s boldly heretical.

In The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936), John Maynard Keynes used the analogy of a beauty contest to explain the actions of most market participants (see also Keynes as investor-speculator). In this pageant, judges choose the six most attractive faces from among 100 photographs.

According to Keynesians, the “naive strategy” is to choose those faces that, in the judge’s opinion, are the most attractive. An allegedly more sophisticated judge attempts to guess other judges’ perceptions of attractiveness and then chooses the photos that best reflect them. This process can become even more complex by assuming that other judges are trying to do the same thing. Keynes summarises the result:

“It is not a case of choosing those [faces] that, to the best of one’s judgment, are really the prettiest, nor even those that average opinion genuinely thinks the prettiest. We have reached the third degree where we devote our intelligences to anticipating what average opinion expects the average opinion to be. And there are some, I believe, who practice the fourth, fifth and higher degrees.”

Two startling implications follow. First, star analysts, “famous fundies” and most “investors” as a whole (“speculators” is a more apt term; see below) base their views of a company and its securities not upon their own analyses of its value, or even upon others’ analyses, but upon what they believe others believe is the consensus of opinion about its popularity. In other words, most “analysts” ground their recommendations – and most investors premise their actions – not upon objective analysis of enduring fundamentals but subjective opinion of short-lived irrelevancies!

It’s not even the analyst’s or investor’s own considered opinion: it’s his (they’re mostly men) guess of others’ opinions. The relatively straightforward exercise of deciding for oneself according to one’s own principles and objectives becomes an immensely complex game of second- and even third-guessing others.

Is this really what you want to do – or pay others to do? The mainstream’s insuperable problem is that opinions and popularity are ever-changing. Hence Keynes’ second implication: in order to profit from the beauty contest, you must make fast money; and to do that you must ignore (because they’re irrelevant for this purpose) companies’ histories, current operations and prospects. As a speculator, you must anticipate other speculators’ actions, buying before they buy and selling before they sell. You must ride waves of investor confidence – and exit before it crashes against the rocks. If you can guess what others are going to think and do, your results will exceed theirs.

Although you’ll win big if you mostly guess reasonably accurately, you’re much more likely to lose even more greatly if even occasionally you guess incorrectly. Buffett agrees: you can’t buy what’s popular today and do well over the long run. That’s why LCO is an investor – not a stock-picker. It’s also why you should shun stock-pickers.

Also Avoid Short-Term “Top Performers” – Instead, Seek Quiet Long-Term Achievers

Since January 2020, LCO has outperformed many others – not by generating mouth-watering gains, but by avoiding gut-churning losses. It’s also matched or surpassed the All Ordinaries Accumulation Index since 1999.

Yet during virtually none of these years did it produce stellar gains; during most of them, its results were pedestrian. In terms of Aesop’s fable, LCO is a long-term tortoise rather than a short-term hare. That’s because, in investment as well as life in general, the odds greatly favour tortoises.

What causes a handful of funds and managers, during almost any 12-month interval, to produce results that greatly exceed that period’s average? The very same thing that subsequently causes them to sag or collapse. Mark Hulbert (“The Year’s Fund Returns Are In – Do They Matter?” The Wall Street Journal, 7 January 2018) finds that it’s NOT skill. It’s probably mere chance; and if it’s not a lucky roll of the dice then it’s the draw of a dodgy set of cards. Most short-term outperformers, in other words, are mere flukes; and a few “pursue wildly risky strategies” that before long go badly awry.

“Though on average they lose, occasionally one of them will hit the jackpot and rise to the top of the annual rankings. By choosing that lucky adviser or manager, investors who invest [“speculators who speculate” is more apt] with the previous year’s top performer are in effect betting that lightning will strike twice. They inevitably get sabotaged by … sky-high risk.”

In short, a single swallow does not a summer make; similarly, one year’s implausibly high return does not long-term outperformance generate.

What, Then, To Do?

Consider a well-to-do couple, family trust, SMSF, etc., which possesses a long-term perspective and the brains, but not the desire or time, to invest on their own behalf. What should they do? Find somebody who’ll invest these funds. But whom to choose? First, Hulbert advises that they should either ignore the latest performance ranking – or else use it to exclude recent implausibly high performers from consideration.

In his words, those who invest prudently and thereby possess strong records of “long-term performance … are hardly ever at the top or bottom of the calendar-year rankings. Slow and steady really does win the race.”

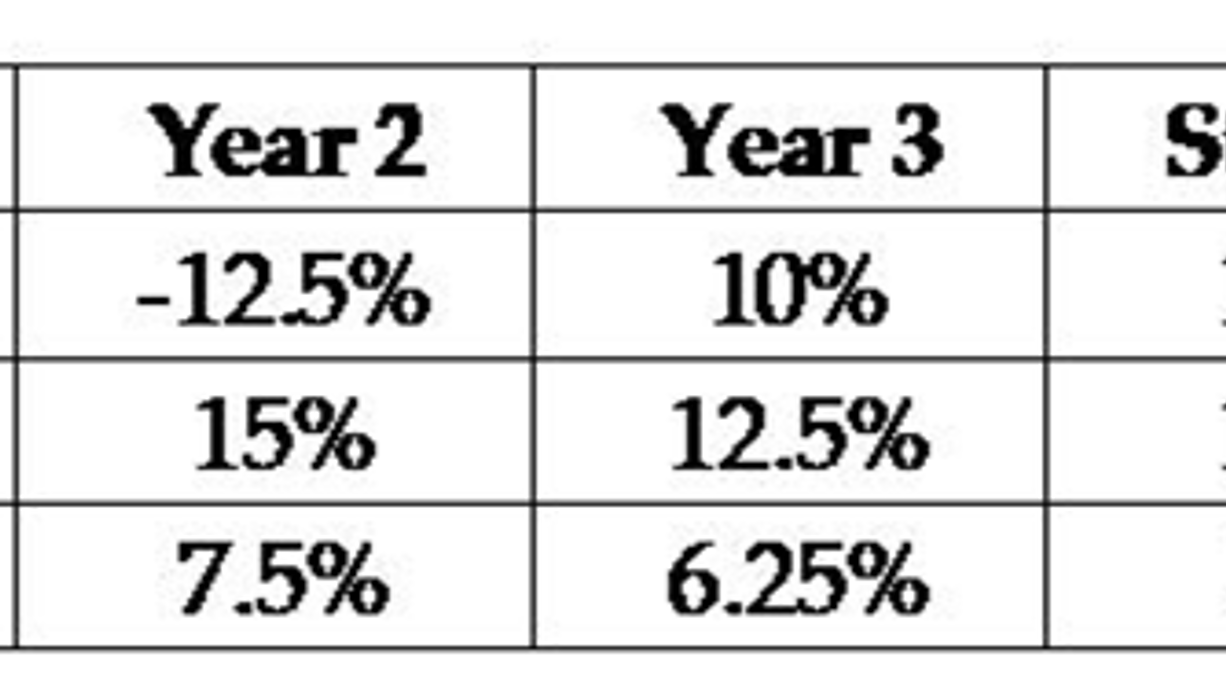

Table 1: Three Funds over Three Years: the Steady Tortoise Beats the Erratic Hares

.png)

This point is fundamental. Consider as a hypothetical but realistic example the three funds in Table 1. (As an aside, the order of each’s results doesn’t affect its three-year compound rate of return.) Fund A greatly outperforms in Year 1 – at whose end, and as a result of laudatory media reports, it likely attracts hefty inflows of funds from speculators. Alas, it incurs a hefty loss (and wins the wooden spoon) in Year 2 – which prompts strong outflows. Speculators who thought they were investors (or investors advised by speculators) bought its units high and sold them low – which is hardly a recipe for success! Fund B greatly lags in Year 1 but excels in Years 2 and 3.

In contrast, in no single year does Fund C lead the field; indeed, each year its return is just one-half of the top-ranked fund’s. Furthermore, in Year 3 it trails the others – and its results fall year by year.

Yet two crucial points distinguish it: first, in none of the three years does it incur a loss; second, from year to year its results are the steadiest (i.e., its standard deviation is the lowest by far). Over the three-year period, these traits make all the difference: Fund C’s three-year return, expressed as an annualised compound rate of return, handily exceeds A’s and B’s.

$100 invested in Fund C at the beginning of Year 1 compounded to ca. $125.64 at the end of Year 3. That exceeds Fund B’s total ($116.44) by almost 8% and Fund A’s ($115.50) by almost 9%. If this disparity persists, then as time passes Fund C will leave A and B ever further in its wake.

Secondly, advises Hulbert, focus on those managers, strategies and vehicles with excellent long-term results. “The clear implication,” he elaborates, is that

“You improve your chances of picking a [winner] by focusing on performance over periods far longer than one year. How long? Our analysis … suggests that even 10 years isn’t enough. Only when performance was measured over at least 15 years were there better-than-50% odds that a top performer would be able to repeat. [Moreover,] when following a top performer over the previous 15 years, you are unlikely to be at the top of the rankings in any given calendar year …”

To Hulbert’s second point I add a twist. Locate investment managers with a track record of 15 years or more, and then ascertain:

- How did they go during the Dot Com Bubble? The boom years before the GFC? Do their results during these intervals suggest that they took undue risks?

- What about their results during the Dot Com Bust and the GFC? The Global Viral Crisis in 2020? The half-year to 30 June 2022? Do their results in the bust confirm that their actions during the boom were unduly risky?

- How many years did they require to recoup significant losses?

The problem is that few managers possess track records of 15-20 or more years; fewer still lose comparatively little during bear markets and crises, and are therefore able to recoup their losses reasonably quickly. The good news is that your list of candidates certainly won’t be long; hence your choice probably won’t be difficult!

Conclusion

Three key attributes distinguish most long-run outperformers. First, and most noticeably, their number is very small. Second, and most importantly, at most times they ignore “experts” and the herd, at critical junctures they defy them – and at all times they think rigorously for themselves. Thirdly, and most subtly, year after year they generate reasonably consistent, almost always positive but rarely top-ranked results. In the short term, they’re plodders or even underachievers; yet by putting the odds on their side, they accumulate excellent long-term results.

It’s vital to emphasise: long-term outperformers’ results within any 12-month interval are usually unremarkable; indeed, and as Table 1 showed, they’re often below-average. Hulbert found that long-run outperformers’

average yearly performance rank … was at the 59th percentile. But that’s a shortcoming only if you’re a thrill seeker who finds it intolerably boring to be merely … at the top of the rankings for very long-term performance … [Accordingly, and assuming that] you are seriously focused on building up wealth over the long term, you should be more than willing to give up the hope of ever being at the top of the calendar-year rankings.

To the mainstream, it’s startling and disconcerting:

- Short-term outperformance doesn’t promote a manager’s long-term outperformance; if anything, it harms it. Similarly, investors who chase short-term outperformance depress their long-term results.

- How much your portfolio advances during booms isn’t overly important; what’s vital is how much it avoids retreating – and especially collapsing – during busts. In a bull market, anybody can look like a genius; the bear market reveals whether he’s really been a dummy all along.

Speculation is a sprint, but investment is a marathon. Yet investors don’t compete against others, and still, less are they trying to win popularity contests; instead, they set their own destination and run their own race. As an investor, Leithner & Company avoids short-term distractions and steers its own long-term course. We don’t try to act brilliantly or outsmart others; nor do we seek to receive the public’s passing plaudits. Instead, for more than 20 years we’ve stuck to rational fundamentals, avoided egregious errors and thereby generated reasonably steady, enduring and cumulatively excellent results for our shareholders.